Çilê Havînê & Çilê Zivistanê

In Ezidism, there are two 40-day fasting (Kurdish: Rojî) periods observed each year, one on the 40 warmest and longest days of summer (“Rojiyên Çilê Havînê”) and one on the 40 coldest and shortest days of winter, (“Rojiyên Çilê Zivistanê”) which are concluded by the feasts of Îda Çilê Havînê (Feast of the Fortieth of Summer) and Îda Çilê Zivistanê (Feast of the Fortieth of Winter) respectively. These fasts are not obligatory for the general Ezidi population but are observed by the members of the central clergy (Baba Şêx, Baba Çawîş, Babê Gavan, Pêşîmam, etc.), the Feqras and Koçeks (seers, oracles, shamans), the Feqîrs/Xerqepoş, the Derwêşes and Qelenders (ascetics), the Şkestîs (monastics) of Laliş as well as any common Ezidi volunteering to partake in the fast. Among the Ezidis of Armenia and Georgia, a family from Mamtacî tribe of the “Ortilî” tribal confederacy is known for observing these fasts every year.[1]Пирбари, Дмитрий (Dimitri Pirbari), 2nd December 2017,Чле хавине и Чле зевестане (Çilê Havînê and Çilê Zivistanê). Официальный Сайт … Continue reading[2]سیدو ختو حسو (٢٠٢١) شرۆڤەکرنا هندەک رێ ورەسم وتێکستێن ئۆلا ئێزدیان (Sîdo Xeto Heso, 2021, Şirovekirina Hindek Rê û Resm û Têkistên Ola … Continue reading[3]Feqîr Hecı̂, Bedelê. Bawerı̂ Û Mı̂tologı̂ya Êzidı̂yan: Çendeha Têkist û Vekolı̂n. Hawar, 2002. pp. 25-27[4]Dîma, Pîr. Êzdîyên Serhedê: Sedsala XIX – Destpêka XX. Translated by Ezîzê Cewo, Weşanxaneya Do, 2011. p. 139[5]پکۆڤان رێسان خانکی (٢٠١٦) هزر و فەلسەفا د ئەدەبياتا دینێ ئێزدياندا (Kovan Rêsan Xankî (2016) Hizir û Felsefa di Edebiyata Dînê Êzdiyanda) … Continue reading[6]Rezan Shivan Aysif, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” pp. 214-216

Date & Feast

In the Ezidi calendar, each day begins and ends at sunset. Therefore, the first day of Çilê Havînê starts at sunset on June 23rd and ends at sunset on June 24th, the fast is held during daylight hours and is broken at sundown.[7]Online interview with a Çilegir of Şingal on 5th August 2024 The 40-day fasting period (“Rojiyên Çilê Havînê) concludes with the Îda Çilê Havînê (Feast of the Fortieth of Summer), celebrated in the Laliş sanctuary during the last three days of the fast, from July 31st to August 2nd. Similarly for Çilê Zivistanê, the first of its forty days commences on the evening of December 23rd, with the first fast being observed from dawn to sunset on 24th December. The fasting period (“Rojiyên Çilê Zivistanê”) concludes with Îda Çilê Zivistanê (Feast of the Fortieth of Summer) which is celebrated on the last two days of the fast from February 1st-2nd.[8]Dimitri Pirbari, 2017

1. Kanûn dibêjit: “Em du mehêt Pedşayî kirîn xelat,

Kanûn says: “We are two months (December & January) that were rewarded by the King (God).

2. Li me dikevin Çile û ‘Erbe’înat,[9]Arabic for “Forty”

The Forties’ fall upon us,

3. Ji hedê wîye li gel me bikelimit Subat!”

Therefore Subat (February) is silent before us!”

– Qewlê Meha, Seb. 28[10]خەلیل جندی رەشۆ (٢٠٠٤) پەرن ژ ئەدەبێ دینێ ئێزدیان (Xelîl Cindî Reşo, 2004, Perin ji Edebê Dînê Êzdiyan) vol 1, p. 267

On the feast days, Laliş sanctuary gets visited by pilgrims from nearby settlements and numerous rituals and ceremonies are carried out in Laliş sanctuary, among which are:[11]Sîdo Xeto Heso, 2021, pp. 67-68

- Lighting of candles (Kurdish: “Vêxistina Çirayan”) at all shrines inside the Laliş valley on every evening.

- Performance of the Sema’ dances (Kurdish: “Semagêran” or “Semakêşan”) each evening. For Îda Çilê Zivistanê, two Sema dances are performed, namely Semaya Şerfedîn and Semaya Qanûnî. For Îda Çilê Havînê three Sema dances are performed: Semaya Şerfedîn, Semaya Qanûni and Semaya Şêşims.[12]Pîr Xelat Elyas Ce’fo, and Zuhêr Ereb Silo. Semaya Dînî Di Êzidiyatîyê da. 2015. p. 30

- Recitations of Ezidi sacred texts including the Qewls, Beyts and Qesîdes, as well as the performance of the Def û Şibab (a type of tambourine and flute) by the Qewals.

- A special dance carried out in front of the Kanîya Spî spring, referred to as Govenda Derê Kanîya Spî, accompanied by the performance of the sacred Def û Şibab instruments.

- Preparation of a sacred type of meal referred to as “Simat” by the custodians (Kurdish: “Micêwir”, “Serderî”) of the shrines inside Laliş sanctuary.

- On the final day of the feasts, the Tawûs/Sinceq effigies are washed and baptised in a ritual referred to as “Ciwankirina Tawûs”.

- In the Ezidi villages, each household slaughters a sacrificial animal (Kurdish: “Serbirr”) for the feast.

Religious Significance

The fasting is observed in honor of God and is believed to have been observed by Ezidi holy figures (“Xas”, “Babçak”, “Xudan”) during the era of the saints in the 12th-13th century. The person partaking in the fast is called “çilegir” (lit. “The Forties’ Faster”) and must fast on each of the 40 days of Çilê Havînê and Çilê Zivistanê.[13]Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 The Çilegir should also fast in the following 20 years too in order to have observed a total of forty 40-day fasts, what is called Çil Çile (lit. “Forty Forties”).[14]Feqîr Hecî, Bedelê, 2002, pp. 26-27

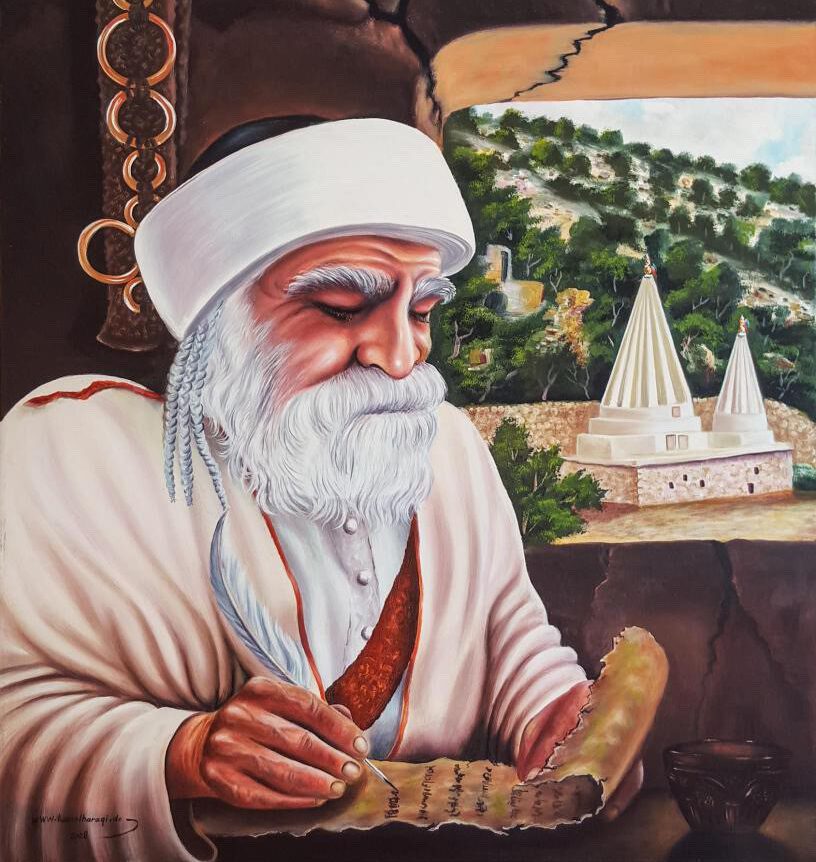

Throughout the 40-day fasting period, the Çilegirs must seclude themselves in solitude at one place, preferably a cell near a temple or a special cave referred to as a Çilexane (lit. “Dwelling of the Forty”).[15]Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 Famous examples of caves of this type is Şikefta Çilexanê (Cave of Çilexanê) at Laliş sanctuary in Duhok Governorate, Iraq, where Şîxadî himself is believed to have observed the Çile and which only Çilegirs and Feqîrs are allowed to enter,[16]Feqîr Hecî, Bedele, 2002, pp. 25-27[17]Pirbari, Dimtri, 2008, Lalişa Nûranî, p. 34 and Ziyareta Çilxanê (Çilxanê shrine) on Lêlûn mountain south of Qibarê village in Efrîn district, Syria.[18]Maisel, Sebastian, 2016, “Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority” pp. 65-66[19]Elî, Mihemed Ebdo, 2008, “Êzdî û Êzdiyetî: Li Bakur Rojavaya Sûriyê” pp. 83-84 The Çilegir must sleep in their designated places of seclusion, rarely leaving during the fasting days. They spend most of their time meditating inside with their heads bowed, only stepping out for ablution or for discussions on Ezidi sacred texts and the lives of saints. At times, the Çilegir may even refrain from speaking altogether. As stated by Dimitri Pirbari (Pîr Dîma Pîrê Behrî), an Ezidi theologian and the head of Ezidi Spiritual Council in Georgia:[20]Dimitri Pirbari, 2017

“The essence of the Çile lies in the remembrance of God with the heart, mortification of the flesh, inner purification, and forgetting worldly desires.”

As a result, the Çilegirs maintain a great deal respect and reputation among the Ezidi society and in the Ezidi religion due to their deep religious devotion. A Qewl forbids hurting them and describes the level of their worship and devotion:

Seb. 43

1. Çilegira ne êşîne, ew jî bi Axretê hîvî ne,

Do not hurt the Çilegirs, they too are hopeful for the Hereafter,

2. Havîn û zivistanê bi rojî ne, û bi wekaz, û bi tizbî ne,

They are fasting in summer and winter, and are holding staffs and beads.

3. Çend cara bi ‘ebadet in û cindiyêt Siltîn e.

Many times they have worshipped [God] and they are the followers of the Ruler (i.e God).

Seb. 44

1. Ew cindiyêt Siltîn bi hîvî ne, bi mehder in,

The followers of God are hopeful, they are in intercession,

2. Li rêya Xwedê û Şîxadî bi cehwer in,

[They are] on the path of God and Şîxadî with glory,

3. Ew jî bi Şêşims mefer in.

They too are in the refuge of Şêşims.

– Qewlê Mersûma Cebêra [21]Şemo Qasim Dinanî, Çend Têkistên Pîroz yên Ola Êzdiyan, vol. 2, Duhok, 2012. p. 34

Most notably, Şîxadî (Şêx Adî ibn Misafir) himself is believed to have secluded himself in a cave, not leaving it for the entire duration of 40 days. When the time came to break the fast, Şîxadî would only eat one raisin (Kurdish: Mêwîj). Şîxadî also observed the fast with his 40 companions called Çilê Şîxadî (lit. “Şîxadî’s forty”).[22]Dimitri Pirbari, 2017

1. Ji Qewlê Şêx Şe’ban e,

From the Qewl of Şêx Şe’ban,

2. Çakiya Şîxadî bo Mêra dana Hed û Sed û Rê û Micade û Çilexane,

The blessings Şîxadî established for Men: Hed û Sed,[23]Literally “Rules and Limits”, which refers to all the codes of conduct and laws in Ezidism. the Path, the Spiritual Striving and the Çilexane,

3. Ji ew paş Şîxadî text ji erda ve guhast ço ezmana.

Thereafter Şîxadî raised his Throne from the earth to the heavens.

– Qewlê Şîxadî û Mêra, Seb. 64[24]Feqîr Hecî, Bedelê, 2002, p. 279

This tradition was also continued by Şîxadî’s great-grandnephew, Melik Şêxisin (Şêx Hesen ibn Şêx Adî II ibn Sexr Ebû’l Berekat), who also observed these fasts with his own forty companions (“Çilê Melik Şêxisin”).[25]Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 These companions are referred to by the title Pîr and their descendants today constitute the bulk of the lineages within the Pîr caste.[26]Pirbari, D. V., & Mossaki, N. Z. (2022). A Yezidi Manuscript – Mišūr of Pir Amar Qubaysi, its study and critical analysis, https://doi.org/10.26907/2619-1261.2022.5.3.66-87, p. 70 As such, it is said that 20 days of both fasting periods belong to Şîxadî and the other 20 days belong to Melik Şêxisin. It is also worth noting that these feasts are considered to be in the category of the feasts dating back prior to the coming of Şîxadî in 12th century. As an example, according to legend, Nûh Pêxember, who built the ark during the great flood, is also said to have observed the forty-day fasting periods.[27]Online interview with a Çilegir of Şingal on 5th August 2024 In 14th-century, not long after the era of the saints, the famous world-traveller Ibn Battuta mentions meeting a certain Sheikh named Abdallah al-Kurdi in a hermitage at the top of Şingal mountain, a historical Ezidi stronghold. Although Ibn Battuta does not mention the Sheikh’s religion, making it difficult to verifiably determine his religion, the description of the Sheikh as an ascetic practicing a forty-day fast at a secluded spot closely aligns with the Ezidi tradition of Çile.[28]H.A.R. Gibb, 2017, The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354, Routledge, vol 2, p. 352

References[+]

| ↑1 | Пирбари, Дмитрий (Dimitri Pirbari), 2nd December 2017,Чле хавине и Чле зевестане (Çilê Havînê and Çilê Zivistanê). Официальный Сайт Духовного Совета Езидов В Грузии. Retrieved August 17, 2024, from https://www.yezidi.ge/home.php?cat=6&sub=5&id=16&mode=blog&lang=ru |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | سیدو ختو حسو (٢٠٢١) شرۆڤەکرنا هندەک رێ ورەسم وتێکستێن ئۆلا ئێزدیان (Sîdo Xeto Heso, 2021, Şirovekirina Hindek Rê û Resm û Têkistên Ola Êzdiyan) pp. 67-68 |

| ↑3 | Feqîr Hecı̂, Bedelê. Bawerı̂ Û Mı̂tologı̂ya Êzidı̂yan: Çendeha Têkist û Vekolı̂n. Hawar, 2002. pp. 25-27 |

| ↑4 | Dîma, Pîr. Êzdîyên Serhedê: Sedsala XIX – Destpêka XX. Translated by Ezîzê Cewo, Weşanxaneya Do, 2011. p. 139 |

| ↑5 | پکۆڤان رێسان خانکی (٢٠١٦) هزر و فەلسەفا د ئەدەبياتا دینێ ئێزدياندا (Kovan Rêsan Xankî (2016) Hizir û Felsefa di Edebiyata Dînê Êzdiyanda) pp. 46-47 |

| ↑6 | Rezan Shivan Aysif, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” pp. 214-216 |

| ↑7 | Online interview with a Çilegir of Şingal on 5th August 2024 |

| ↑8 | Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 |

| ↑9 | Arabic for “Forty” |

| ↑10 | خەلیل جندی رەشۆ (٢٠٠٤) پەرن ژ ئەدەبێ دینێ ئێزدیان (Xelîl Cindî Reşo, 2004, Perin ji Edebê Dînê Êzdiyan) vol 1, p. 267 |

| ↑11 | Sîdo Xeto Heso, 2021, pp. 67-68 |

| ↑12 | Pîr Xelat Elyas Ce’fo, and Zuhêr Ereb Silo. Semaya Dînî Di Êzidiyatîyê da. 2015. p. 30 |

| ↑13 | Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 |

| ↑14 | Feqîr Hecî, Bedelê, 2002, pp. 26-27 |

| ↑15 | Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 |

| ↑16 | Feqîr Hecî, Bedele, 2002, pp. 25-27 |

| ↑17 | Pirbari, Dimtri, 2008, Lalişa Nûranî, p. 34 |

| ↑18 | Maisel, Sebastian, 2016, “Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority” pp. 65-66 |

| ↑19 | Elî, Mihemed Ebdo, 2008, “Êzdî û Êzdiyetî: Li Bakur Rojavaya Sûriyê” pp. 83-84 |

| ↑20 | Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 |

| ↑21 | Şemo Qasim Dinanî, Çend Têkistên Pîroz yên Ola Êzdiyan, vol. 2, Duhok, 2012. p. 34 |

| ↑22 | Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 |

| ↑23 | Literally “Rules and Limits”, which refers to all the codes of conduct and laws in Ezidism. |

| ↑24 | Feqîr Hecî, Bedelê, 2002, p. 279 |

| ↑25 | Dimitri Pirbari, 2017 |

| ↑26 | Pirbari, D. V., & Mossaki, N. Z. (2022). A Yezidi Manuscript – Mišūr of Pir Amar Qubaysi, its study and critical analysis, https://doi.org/10.26907/2619-1261.2022.5.3.66-87, p. 70 |

| ↑27 | Online interview with a Çilegir of Şingal on 5th August 2024 |

| ↑28 | H.A.R. Gibb, 2017, The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354, Routledge, vol 2, p. 352 |