Abstract

This article aims to delve into the religious and symbolic significance of snakes in Ezidism, a religion indigenous to Kurdistan, and their role in Ezidi mythology. Additionally, the holy and historical figure of Şêx Mend, who is recognized as the Xudan (patron, protector, lord, master) of snakes in Ezidi tradition, will be explored. Through an in-depth analysis, this article provides a concise account of Şêx Mend’s biography and scrutinizes the references to him in Ezidi tradition and in historical documents.

The Religious Significance of Snakes in Ezidism

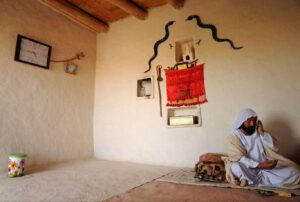

In Ezidism, snakes, especially the black snakes (‘marê reş’), hold a significant place as a revered symbol and animal. They can be found engraved or drawn on the entrances of houses and temples, and are regarded as symbols of immortality and renewal, as well as protectors against evil. As a result, there exists a religious prohibition against harming them. [1]Aysif, Rezan Shivan, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” pp. 266-268

The snake is regarded as a punisher of evil and immorality. It is believed that engaging in unethical behaviour can result in retribution from the snakes. For instance, if an Ezidi eats food in front of a hungry person without offering to share it with them, they will be visited by a snake in their dreams, which will inflict nightmares upon them. This belief is another display of the strong emphasis on ethics and morality in the Ezidi religion, where adherents are expected to show compassion and generosity towards others, especially those who are less fortunate. This is also dictated in Ezidi sacred texts. [2]Khalaf, Diar & Demir, Hayri, 2013, “Mythos und Legende der Şêx Mend und das symbol der Schlange”

1. Fere li ser mêrê meclisê,

The host has the duty,

2. Rojê sê cara li dîwana xwe bipirsî,

To ask his dîwan (guest room) three times a day,

3. Gelo kê xwariye û kî maye birsî,

Who has already eaten and who is still hungry?

– Qewlê Şeqserî

Snakes, as well as scorpions, are also believed to punish the wicked.

1. Li ba êrifa we diyar e,

From the mind one is clear,

2. Hincî dilê bi xezebe û bi jehr e,

Those whose hearts are filled with malice and malevolence,

3. Ewî mala xwe avakiriye bo dûpişkan û mar e.

Have their home built for snakes and scorpions.

– Qewlê Miştaqê Sê Borim

Şêx Mend – Holy Being and Historical Figure

Historical Biography

The Xudan (patron, protector, lord, master) of snakes in Ezidi tradition is recognized as Şêx Mendê Fexran (‘Şêx Mend [son] of Fexr’), also known as Şêx Mend Paşayê Helebê (‘Şêx Mend the Pasha of Aleppo’), or more commonly, just Şêx Mend. He is a notable Ezidi holy and historical saintly figure, who ruled over the Emirate of Kilîs/Aleppo.[4]Ibid Şêx Mend was the eldest son of Şêx Fexredîn, a prominent Ezidi holy figure and one of the four primary progenitors of the Şemsanî clan of the Ezidi Sheikhs who lived originally in the village of Mkeris (Mikêris), which is today located north of Lalish in the Atrush district of modern-day Duhok governorate. [5]Khatari, Dawd Murad “من اثار الايزيدية. . .الحلقة الاولىالباحث . داود مراد ختاري” [Video]. Ezidi Researcher Dawd Murad Khatari visits Mkeris … Continue reading[6] Şêx Fexrê Adiyan: Fîlosof û xasê ola Êzdiyatiyê. (2009, November). Dengê Êzidiyan Oldenburg, pp. 187, 230, 288 Şêx Fexredîn was the brother of Şêx Şems, Nasirdîn and Sicadîn, and they were the four sons of Êzdîne Mîr. These four brothers are recognized as the progenitors of the four primary Şemsanî Sheikh lineages. [7]Ibid. p. 230 It is worth noting that according to Ezidi belief, these four brothers are considered to be the avatars of four of the seven Angelic Beings. When referring to their divine versions, they normally get designated by the title “Melek”; i.e they are referred to as Melek Fexredîn, Melek Şemsedîn, Melek Nasirdîn, and Melek Sicadîn.

The children of Şêx Fexredîn are composed of his two sons, Şêx Mend and Şêx Bedir, while some dispute the status of Aqûbê Mûsa as his third son, given that it is uncertain if he was adopted or was from another wife. Their descendants continue to exist and form two of the three sublineages of the Fexredîn lineage. Additionally, Şêx Fexredîn had a daughter named Xatûna Fexra, whose descendants form the third sublineage (Şêxêt Xatûna Fexra). [9]Ibid. p. 186

Şêx Mend would eventually gather around him some tribes under his service and migrate from his home in the modern-day Bahdinan region to Aleppo, where he would be appointed as the Lord of all Kurds in Aleppo and Damascus regions, as written in the book Sharafnama, a book about Kurdish history written in 1596 by the 16th-century historian and Emir of Bitlis, Sharaf al-Din Bitlisi: [10]Bedlîsî, Şerefxanê, Şerefname: Dîroka Kurdistanê [Wergera Kurmancî], pp. 267-269

“Mend initially managed to gather around him a tribe of Kurds and went with them to Damascus and Egypt and entered the service of the Ayyubid rulers. They gave him the town of Kusayr near the Antakya Province. Mend and his men settled there in the winter. The venture did not stop there; A group of Yezidi Kurds who had lived in that land before also gathered around Mend. This, in turn, led to the exaltation of his glory and the increase of his influence day by day. Kurds came to him from all sides; also the Kurds living near Kilis and Cun joined him. The great Ayyubid rulers showed great interest in him and appointed him Beylerbey (‘lord of lords’) of all Kurds in Damascus and Aleppo; they gave him the complete freedom to lead this community, to decide and settle matters. Thus, they promoted him to the highest military and administrative rank.”

From the book, we also learn that Ezidis had a large presence in these regions. It mentions that the Sheikhs of the Ezidis from the regions between Hama and Maraş initially competed with Mend over this high administrative position of power, but that they later also submitted to Mend:

“At the beginning of these events, the sheikhs of the Yezidi Kurds who were spread between the regions of Hama and Maraş clashed with him over this lofty position. This situation sometimes even led to the drawing of swords and war. But Mend prevailed over them and made them submit to him, sometimes in a harsh manner, sometimes in a soft manner, sometimes by pressure, sometimes by kindness. He eventually got what he wanted and all the Kurds in that land submitted to his absolute rule.”

The book’s description of Mend can raise some uncertainties about whether it refers to the same Şêx Mend recognized by the Ezidis since Sharaf al-Din does not specify Mend’s religious affiliation, although he does specify the group of Kurds from the Kusayr region who assembled around him as Ezidis. Furthermore, the account notes that Mend’s brothers were Shams ad-Din (Şemsedîn) and Baha ad-Din (Behdîn), whom, according to the text, the rulers of Hakkari and Amadiya principality were descended from. The rulers of Hakkari were descended from Shams ad-Din, hence the name “Şemo” attributed to them by the Kurds, while the rulers of Amadiya were descended from Baha ad-Din, after whom the region of Bahdinan is named. [11]Ibid These details are inconsistent with the genealogical tree of Şêx Mend presented in Ezidi tradition, which only lists Şêx Bedir and occasionally Aqûbê Mûsa as his brothers.

However, the book “Durr al-Habab fi Tarikh A’yan Halab,” written by Radhi al-Din bin Ibrahim bin Yusuf al-Halabi, also known as Radhi al-Din ibn al-Hanbali (1502 – 1563 CE), a 16th-century historian hailing from Aleppo, sheds some light on the matter. This work predates Sharafnama and provides biographical accounts of notable figures from Aleppo, and it mentions a certain Emir of the Kurds, Izz al-Din ibn Yusuf al-Kurdi al-Adawi, who ruled during the transition from Mamluk to Ottoman rule. According to Radhi al-Din’s account, Izz al-Din ibn Yusuf al-Kurdi al-Adawi belonged to a religious group affiliated with Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir, which clearly indicates his religious affiliation as having been Ezidism. Radhi al-Din’s account goes on to state that Izz al-Din was a member of the House of Sheikh Mend, whose reputation as healers of snake bites drew in those afflicted to seek treatment. According to the same account, he would provide a remedy for the victims by offering them bread that he had blessed himself, which had the power to heal their wounds. [13]Ibn al-Hanbali, Radhi al-Din, Durr al-Habab fi Tarikh A’yan Halab, Al-Fakhuri, Mahmud & Abbara, Yahya (eds.), Damascus, 1974. Vol. 1, pp. 890-894 Such curative powers are associated with the Sheikhs of the Sheikh Mend lineage, who are sought out by Ezidis in need of treatment for snake bites, as will be discussed in greater detail below.

Although in Şerefname, a certain Ereb is mentioned as the son of Şêx Mend. In Radhi al-Din al-Hanbali’s report, there is in fact no such mention of Ereb being Şêx Mend’s son and his descent from the house of Şêx Mend is rejected. Instead, it is mentioned that there was an enmity between the house of Şêx Mend (represented by Şêx Îzz el-Dîn) & the house of Ereb (represented by Qasim & Hebîb Beg) which had a religious background, as the former are Yezidis & the latter Muslims. Şerefname gives a misinformation here. Presumably the writer relied on descent from Şêx Mend as a legitimisation for ruling Kilis since he’s the founder. Also, al-Hanbali rejects Ereb’s descent from Şêx Mend’s house. In other words, Radhi al-Din’s work can be considered more authentic and his account refutes the later account in Şerefname on Ereb being an offspring of Şêx Mend.[14]Ibid

These details provided in Radhi al-Din’s book are consistent with Ezidi traditions preserved until today and allow us to confirm that the Mend who ruled Kilis, Kusayr and Aleppo, and is mentioned in Sharafnama, is indeed the same Şêx Mend known by Ezidis. We can also substantiate that the position of Emir of Kurds continued to be held by Sheikh Mend’s family for centuries, from the Ayyubid era to the Ottoman period, and that they remained a religiously practising Ezidi dynasty of the Sheikh caste throughout this period.

In the Ezidi tradition, Sheikh Mend is also acknowledged as Şêx Mend Paşayê Helebê (Sheikh Mend the Pasha of Aleppo), which aligns with the account in Sharafnama of his rise to power in Aleppo. Moreover, the story in Sharafnama of his migration to the Levant from the Hakkari region is consistent with the Ezidi tradition, which identifies Mikêris, situated north of Lalish near Mount Dasin in the Atrush district, as the ancestral village of the Şemsanî family and records that each holy man moved to his designated location, which, in the case of Sheikh Mend, was Aleppo. [15]See “Çîroka Siltanî Zeng û Şîxadî, Bedredîn, Şêx Hesen û Şêx Mend (The Story of the Zangid Sultan and Sheikh Adi, Bedredin, Sheikh Hesen and Sheikh Mend)”, recited in 1999 … Continue reading

Sheikhs from the Priestly Lineage of Şêx Mend

Sheikhs belonging to the Şêx Mend lineage (Şêxêt Şêx Mend) are believed to possess special powers over snakes and receive training in handling them from a young age. Additionally, they are taught how to naturally heal and treat snake bites. Hence, in the event of a snake bite, the Ezidis typically seek the services of a Sheikh hailing from the Şêx Mend clan to treat the affliction. Services of the Sheikhs of Şêx Mend are sought also when a house is infested with snakes, whereupon they bring a bowl of water and recite the Prayer of the Scorpion and the Snake (Duaya Dûpişk û Mar) three times while moving their finger in the bowl of water. This water is later to be sprinkled around the home in the belief that it will stop the snakes from coming back. The same services with Scorpions are sought from Pîrs of the lineage of Pîr Cerwan, the Xudan of Scorpions.[16]Aysif, Rezan Shivan, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” pp. 243-244

1. Şêx Mendî Fexiran e,

Şêx Mend of Fexir,

2. Pîrê Cerwan e,

Pîrê Cerwane,

3. Heke dubişk e,

If it is a scorpion,

4. Heke mar e,

If it is a snake,

5. Di serî de bike befsar e,

They control them,

6. Berde çol û çolbeyaran,

Free them to moors and the wilderness,

7. Heya em sibê bibin hişyar e,

Until we wake up in the morning,

8. Û roj li me bibe diyarî ye.

And the sun rises on us.

–Duaya Dûpişk û Mar

It is noteworthy that various Ezidi priestly clans and lineages have totem animals that they are believed to hold a special power over. They are expected to adhere to taboos against causing harm to their respective totem animal and consuming its flesh. Some examples include the Sheikhs of Şêx Zendîn lineage, whose totem animals are hares, and the lineage of Şêx Amadîn who are forbidden from eating roosters for the same reasons. In certain circumstances, such priestly clans may receive instructions on how to handle the animal safely and treat wounds inflicted by them, such as the Pîrs of Pîr Cerwan who are trained to handle scorpions in the same way Sheikhs of Şêx Mend are trained to handle snakes. [17]Omarkhali, Khanna. (2008). On the Structure of the Yezidi Clan and Tribal System and its Terminology among the Yezidis of the Caucasus. Journal of Kurdish Studies. 6. 104-119. 10.2143/JKS.6.0.2038092.

Snakes in Ezidi Mythology and Their Symbolism

Snakes appear in many religious and folk stories, perhaps the most well-known being that of the snake who saved Noah’s ark during the great flood by blocking a leak to prevent water from leaking in, thus gaining the snake the credit as the saviour of all humans and animals. [19]Aysif, Rezan Shivan, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” p. 139

1. Sefîne qul bû, av kete ser e,

The ship got a leak, water poured through in,

2. Marî xerê xwe dana ber e.

The snake coiled itself over it.

– Qewlê Afirîna Dinyayê

According to Ezidi mythology, the snake achieved immortality by drinking from the Water of Life (Ava Jiyanê/Ava Hêwanê), hence its role as the keeper and protector of the water of springs. The Water of Life is a mythological water that is believed to contain miraculous properties. It is said to possess the power to grant immortality to those who drink it. As an example, the two brothers, Xidir Îlyas and Xidir Nebî, are believed to be immortals due to having drunk this water. The association of the snake with immortality is also owed to the fact that they can infinitely shed their skin and appear forever youthful. For this same reason, since it sheds their old skin and starts a new life, they are also seen as a symbol of renewal and are associated with the yearly season of spring when nature renews itself. [21]Ibid. pp. 266-268

[the_ad id=”27681″]

As such, the beginning of the spring season coincides with the Sheikhs of Şêx Mend making rounds in the villages with their snakes. Ezidis go up to them, kiss their hand and touch their snake. An entrance of a Sheikh with his black snake inside one’s home is considered to be a sign of renewal, healing, good, bestowal and of protection against disease and poverty. [22]Ibid. p. 267

Şêx Mend and the Hewêrîs

The Hewêrî, a large Ezidi tribe whose territory is centred in the Simele and Zakho districts of the Duhok region, honour Şêx Mend as their Xudan and attribute their success in withstanding the pressure to convert to Islam to Şêx Mend. Şêx Mend is believed to have saved the tribe from being led astray to Islam. The Hewêrîs still retain a folk tale dating back to the era of Sheikh Adi, in which the tribe, dissatisfied with a decision made by the Mîr, contemplated abandoning their faith. In response, Sheikh Adi proclaimed that whoever could prevent them from straying can take them as their Mirîds. He dispatched saints to the Hewêrî tribe, yet none were successful in persuading them otherwise. As nomads, the Hewêrîs were wandering towards Mount Cudi (Çiyayê Cudi) or the Hasana Valley (Geliyê Hasana). Sheikh Mend pledged to intervene and decided to take the initiative to halt their movement and persuade them to remain loyal. Upon the tribe’s arrival at the hill, Sheikh Mend transformed himself into a large black snake, intercepted them at Hasana valley and was able to persuade them to remain loyal. Sheikh Mend then lived among them for seven years before returning to Lalish. It is said that the tribe was henceforth called “Hewêrî,” a name comprising of two Kurdish words, “Hew” and “Wêr.” Together, the phrase “Hew wêrî” translates from Kurdish to “No longer dared”, referring to when they were deterred by Şêx Mend from abandoning their religion. [24]For the whole story narrated by Şêx Mehmûd, see: Khalaf, Diar & Demir, Hayri, 2013, “Mythos und Legende der Şêx Mend und das symbol der Schlange”

[the_ad id=”27681”]

For this reason, Sheikh Mend is highly revered in the Hewêrî tribe today. He is the patron Xudan and saint of this tribe and the Sheikhs of Hewêrîs are thus until today the Sheikhs of the Sheikh Mend lineage. Sheikhs of Sheikh Mend also have the Simoqî tribe of Shingal as their Mirîds, and the reason for this is thought to be because Simoqîs are an offshoot of the Hewêrî tribe. [25]Ibid

Şêx Mend, Şîxadî and the Serpent

In a “Çîrok” (story, tale) among the Ezidis of Armenia, recorded from the narration of an Ezidi named “Pristav Nado” from the Sipkî tribe, by Vilchevsky, who published a Russian translation of the narration in 1930, there is a storyline about a giant winged snake subordinated to Şêx Fexir. This snake is standing in the water on the back of a giant tortoise, which lies on the seabed and bears the entire weight of all animals, who are all subordinated to the tortoise, which is itself subordinated to Sheikh Mend. The story narrates that Sheikh Mend has under his subordination all the animals, whether living on the earth, in the water or the sky, and they come to Sheikh Mend with the complaint about the snake which oppresses all the other animals. Sheikh Mend then goes to confront the snake and fight it with his stick. [26]Вильчевский О. Л. <<Очерки по истории езидства>> (Vilchevsky O. L., “Essays on the history of Yezidism”. 1930[27]For the full English translation, see: Omarkhali, Khanna. (2017). “The Yezidi Religious Textual Tradition: From Oral to Written. Categories, Transmission, Scripturalisation and Canonisation of … Continue reading

[the_ad id=”27681″]

In a sacred poem, called Qesîda Şîxadî (Qasida of Sheikh Adi), there is also a brief reference to a confrontation between Şîxadî and a serpent. This Qesîde was created in the Arabic dialect of Bashiqa and Bahzan, two Arabic-speaking Ezidi villages near Mosul, and is preserved orally among the Qewals and the Pêşîmam family in Bashiqa and Bahzan. It has also been preserved in writing on the Mişûr (sacred manuscript) of Pîr Xetîb Pisî and a variant of this Qesîde was published in 1911 by the German writer Rudolf Frank. In a passage of the Qesîde, Şîxadî briefly narrates in first-person about being confronted by a snake. According to the variant written on the Mişûr, he turns the serpent to dust and hits the rocks with his fist, causing water to burst from it:[28]Ibid. pp. 385-388[29]Dimitri Pirbari, Nodar Mossaki & Mirza Sileman Yezdin (2020) A Yezidi Manuscript:—Mišūr of P’īr Sīnī Bahrī/P’īr Sīnī Dārānī, Its Study and Critical Analysis, Iranian Studies, … Continue reading

“I am the one to whom came a beast of prey and there was neither […] nor […] in it,

It became of stone,

I am the one to whom a serpent came,

And by my will I made it dust,

I am the one who hit the rocks with my fist and made them fear,

And let burst out from their sides sweet water.”

In the variant recorded in 1911 by Rudolf Frank, however, Şîxadî is instead armed with a spear, which he uses to throw at the serpent from whose mouth the water flows out as a result.

“They tried to shame me,

Through a huge snake, which let me down.

I had a spear in my hands, which I threw at it,

And then water flowed from her mouth.”

This theme of a victorious holy figure, mythical hero or god battling with a serpent or dragon is one of the motifs shared universally between the mythologies of the Indo-European peoples. Some examples include Vedic mythology, according to the Rig Veda, the god Indra defeats the serpent Vritra, who was causing a drought by trapping all the water in his mountain lair. After slaying Vritra, Indra pierced a path for water and split the innards of the mountains. This story is strikingly analogous to the aforementioned storyline from the Qesîde, in which Sheikh Adi, after defeating the serpent, also causes water to be released or burst out. In Greek mythology, the god Apollo slays a serpent by the name of Python. This motif also appears in Norse mythology, where the god of thunder Thor slays the giant serpent Jörmungandr, who was living in the waters surrounding the realm of Midgard.[30]West, M. L., “Indo-European Poetry and Myth” (Oxford, 2007), pp. 250, 256-258 This serves as one of the many testimonies to the preservation of Indo-European elements and an Indo-Iranian substratum in the Ezidi myths despite being under the threat of violence and extermination from the neighbouring Muslims for centuries.

Snakes in Kurdish culture

In the broader Kurdish culture, snakes or serpents have a central role in several folk myths. One of the most well-known examples is the mythical half-human and half-snake creature in Kurdish folklore, Shahmaran (‘queen of snakes’), who symbolizes wisdom, immortality, fertility, and knowledge. [32]Deniz, Dilsa. (2021). The Shaymaran: Philosophy, Resistance, and the Defeat of the Lost Goddess of Kurdistan. Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 22. 221-248. 10.1558/pome.38409. Shahmaran does not appear in any religious stories of the Ezidis or in any orally-transmitted sacred texts. However, in the tribal register of Mişûr of Pîr Xetîb Pisî, one of the tribes listed as Pîr Xetîb Pisî’s Mirîds (disciples/followers) is the “Mar Shahmaran” tribe (‘qabīlāt mār shahmarān’). It is intriguing to note that the manuscript, despite being written in Arabic, uses the Kurdish word “Mar” to refer to snake, which suggests that “qabīlāt mār shahmarān” could be translated as “The Tribe of the Snake of Shahmaran”. Unfortunately, this tribe appears to have vanished from pages of history, and there is no known report of a Kurdish tribe with this name still existing today. Additionally, no other historical documents have been discovered mentioning this tribe, thus providing us with limited information about their existence. [33]Omarkhali, Khanna. (2017). “The Yezidi Religious Textual Tradition: From Oral to Written. Categories, Transmission, Scripturalisation and Canonisation of the Yezidi Oral Religious Texts”, … Continue reading

In many Kurdish tribes and regions, killing snakes has been traditionally prohibited, and in certain Kurdish religions such as Alevism, snakes are held in high esteem. Although the subject has not been adequately researched, there are still indications of the reverence for snakes among Muslim Kurds, sometimes with noticeable Ezidi influences.

[the_ad id=”27681″]

For instance, in a 2013 interview with Hussein Bazirki, a veteran Peshmerga fighter from Bazirka village in Amedi, Duhok Governorate, a predominantly Muslim Kurdish area, he recounted a story his grandfather told him to comfort him after a black snake slithered away from his grandfather’s legs and to explain why black snakes should never be harmed: [35]A Peshmerga and the United States. (n.d.). Retrieved March 24, 2023, from https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/170920131

“When Noah tried to save the world, his ark hit a rocky mountain and it began to take on water. Not knowing what to do, the black snake of the vessel rushed to the scene and covered the hole to save the ship and humanity. So we should never harm black snakes. There is goodness in them.“

The account of the ark’s rescue by a black snake during the catastrophic flood is a narrative unique to the Ezidi religious tradition. It is plausible that despite the Islamization of the originally Ezidi Kurdish population in the area, this story has been passed down to their Muslim descendants and continued to be told as a folk story and served as an explanation for the prohibition against harming black snakes. Among the Kurds of Balakayati, there also exists a prohibition against harming black snakes and they are seen as friendly animals who don’t harm anyone. If they are killed, it is believed that their mother, father or mate will take revenge. [36]Interview with a native from Rûst village in Balakayati region, conducted on March 2023

Snakes in Rêya Heqî Alevism

Alevis are a religious community of Kurds and Turks primarily located in Central Turkey and Northern Kurdistan. For the purpose of this study, our attention will be directed towards the religious tradition of Kurdish Alevis, primarily situated in the Dêrsim province and known as Rêya Heqî Alevism, which shares many striking similarities with Ezidism that date back to a common pre-Islamic tradition and have been established in the latest studies. [37]See more: “Turgut, Lokman. “Ancient Rites and Old Religions in Kurdistan.” Studia Kurdica 1 (2013).” and “Kreyenbroek, P., & Omarkhali, K. (2021). ‘Kurdish’ … Continue reading

Within Kurdish Alevism, snakes hold a sacred status, they can commonly be found engraved on tombstones and it is strictly prohibited to harm them as it is believed that they carry within them reincarnated human souls. Additionally, there exist holy objects that are symbolic of snakes, referred to as ‘çuwê heqî’ (God’s stick) or ‘tarix’ and ‘tarık’ which are thin wooden sticks with carvings at the top in the shape of a snake’s head. These objects are regarded as physical representations (material world of ‘Zahir‘) of ‘moro şia‘ (the black snake) or ‘moro sur‘ (the red snake). They are regarded as relics from the world of Batin (the spiritual world where supernatural beings dwell) and are considered to be mystical and dangerous objects, possessing miraculous powers and the capability to transform into snakes or dragons during ‘cem’ ceremonies. For this reason, they are solely kept among priestly groups (raybers, pirs, murşids). These objects are also believed to possess healing properties and are used to treat people who suffer from paralysis or psychological afflictions. [38]Gültekin, A. K. (2019). Kurdish Alevism. Working Paper Series of the HCAS ‘Multiple Secularities – Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities. https://doi.org/10.36730/2020.1.MSBWBM.18[39]Ahmet Kerim Gültekin (2022) Kemerê Duzgi: The Protector of Dersim (pilgrimage, social transformation, and revitalization of the Raa Haqi religion), British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, DOI: … Continue reading[40]Other Customs, Stories, and Beliefs of the Munzur Valley (no date) The Alevis of the Munzur Valley. Available at: http://www.munzurvalley.com/other-customs#customs1 (Accessed: April 2, 2023)[41]Interview with a native Zaza Alevi from Palu, Elazığ province

[the_ad id=”27681″]

One of the most well-known of these sacred sticks is called “Kiştim Evliyası” (Saint of Kiştim), believed to have been a piece of the Rod of Moses. It is preserved in a green cloth bag suspended from a wooden pillar in the sanctuary of the village of Kiştim near Erzincan. The stick is used during ceremonies on the feast of Xizir Ilyas, which is preceded by a three-day fast. On this day thousands of Alevis perform a pilgrimage to the village to see the sacred stick. [42]DIMLĪ. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/dimli

Drawing from the veneration of snakes within the religious tradition of Kurdish Alevis and Ezidis, it can be postulated that their respective traditions trace back to a shared, pre-Islamic religion wherein a cult of snakes likely held a prominent role, and which likely was distinct from Zoroastrianism, a religion that regards snakes as one of the evil animals. [43]Mahnaz Moazami, “MAMMALS iii. The Classification of Mammals and the Other Animal Classes according to Zoroastrian Tradition,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2015, available at … Continue reading While the sources that offer detailed insight into the pre-Islamic religious practices of the Kurds are scarce and vague, it is possible to infer the presence of such faith through analysis of the enduring customs and beliefs that persist among Islamized populations, as well as from certain traditions among the Yarsanis, Alevis, and Ezidis. Accordingly, it may be achievable to reconstruct certain facets of this pre-Islamic faith.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Aysif, Rezan Shivan, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” pp. 266-268 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Khalaf, Diar & Demir, Hayri, 2013, “Mythos und Legende der Şêx Mend und das symbol der Schlange” |

| ↑3 | Please contact Robert Leutheuser at robleutheuser@gmail.com for permission for any and all uses |

| ↑4 | Ibid |

| ↑5 | Khatari, Dawd Murad “من اثار الايزيدية. . .الحلقة الاولىالباحث . داود مراد ختاري” [Video]. Ezidi Researcher Dawd Murad Khatari visits Mkeris village. Retrieved January 15, 2018, from (https://youtu.be/X43UZkmJhe4). Higher quality version of the video is also available on his official Facebook page (https://fb.watch/jNiKkPvm52/) |

| ↑6 | Şêx Fexrê Adiyan: Fîlosof û xasê ola Êzdiyatiyê. (2009, November). Dengê Êzidiyan Oldenburg, pp. 187, 230, 288 |

| ↑7 | Ibid. p. 230 |

| ↑8 | Attribution: Image courtesy of an anonymous owner |

| ↑9 | Ibid. p. 186 |

| ↑10 | Bedlîsî, Şerefxanê, Şerefname: Dîroka Kurdistanê [Wergera Kurmancî], pp. 267-269 |

| ↑11 | Ibid |

| ↑12 | Attribution: Slemanibob, Sharaf Khan Bidlisi Statue at Slemani Public Park, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

| ↑13 | Ibn al-Hanbali, Radhi al-Din, Durr al-Habab fi Tarikh A’yan Halab, Al-Fakhuri, Mahmud & Abbara, Yahya (eds.), Damascus, 1974. Vol. 1, pp. 890-894 |

| ↑14 | Ibid |

| ↑15 | See “Çîroka Siltanî Zeng û Şîxadî, Bedredîn, Şêx Hesen û Şêx Mend (The Story of the Zangid Sultan and Sheikh Adi, Bedredin, Sheikh Hesen and Sheikh Mend)”, recited in 1999 for Philip Kreyenbroek by Sheikh Osman son of Sheikh Birahim, who belongs to Şêxûbekir lineage of Sheikhs and comes from Nusaybin region. The Kurmancî transcription and English translation of the story were published in the book “God and Sheikh Adi are Perfect: Sacred Poems and Religious Narratives from the Yezidi Tradition” (pp. 112-118) |

| ↑16 | Aysif, Rezan Shivan, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” pp. 243-244 |

| ↑17 | Omarkhali, Khanna. (2008). On the Structure of the Yezidi Clan and Tribal System and its Terminology among the Yezidis of the Caucasus. Journal of Kurdish Studies. 6. 104-119. 10.2143/JKS.6.0.2038092. |

| ↑18 | Please contact Robert Leutheuser at robleutheuser@gmail.com for permission for any and all uses |

| ↑19 | Aysif, Rezan Shivan, 2021, “The Role of Nature in Yezidism: Poetic Texts and Living Tradition” p. 139 |

| ↑20 | Attribution: Levi Clancy, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

| ↑21 | Ibid. pp. 266-268 |

| ↑22 | Ibid. p. 267 |

| ↑23 | Please contact Abdulvahap Demir at v.demir4782@gmail.com for permission for any and all uses |

| ↑24 | For the whole story narrated by Şêx Mehmûd, see: Khalaf, Diar & Demir, Hayri, 2013, “Mythos und Legende der Şêx Mend und das symbol der Schlange” |

| ↑25 | Ibid |

| ↑26 | Вильчевский О. Л. <<Очерки по истории езидства>> (Vilchevsky O. L., “Essays on the history of Yezidism”. 1930 |

| ↑27 | For the full English translation, see: Omarkhali, Khanna. (2017). “The Yezidi Religious Textual Tradition: From Oral to Written. Categories, Transmission, Scripturalisation and Canonisation of the Yezidi Oral Religious Texts”, pp. 125-127 |

| ↑28 | Ibid. pp. 385-388 |

| ↑29 | Dimitri Pirbari, Nodar Mossaki & Mirza Sileman Yezdin (2020) A Yezidi Manuscript:—Mišūr of P’īr Sīnī Bahrī/P’īr Sīnī Dārānī, Its Study and Critical Analysis, Iranian Studies, 53:1-2, 223-257, DOI: 10.1080/00210862.2019.1669118 |

| ↑30 | West, M. L., “Indo-European Poetry and Myth” (Oxford, 2007), pp. 250, 256-258 |

| ↑31 | Attribution: Levi Clancy, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

| ↑32 | Deniz, Dilsa. (2021). The Shaymaran: Philosophy, Resistance, and the Defeat of the Lost Goddess of Kurdistan. Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 22. 221-248. 10.1558/pome.38409. |

| ↑33 | Omarkhali, Khanna. (2017). “The Yezidi Religious Textual Tradition: From Oral to Written. Categories, Transmission, Scripturalisation and Canonisation of the Yezidi Oral Religious Texts”, pp. 383-384 |

| ↑34 | MikaelF, derivative work: Gomada, Şahmaran, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

| ↑35 | A Peshmerga and the United States. (n.d.). Retrieved March 24, 2023, from https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/170920131 |

| ↑36 | Interview with a native from Rûst village in Balakayati region, conducted on March 2023 |

| ↑37 | See more: “Turgut, Lokman. “Ancient Rites and Old Religions in Kurdistan.” Studia Kurdica 1 (2013).” and “Kreyenbroek, P., & Omarkhali, K. (2021). ‘Kurdish’ Religious Minorities in the Modern World. In H. Bozarslan, C. Gunes, & V. Yadirgi (Eds.), The Cambridge History of the Kurds (pp. 533-559). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108623711.022″ |

| ↑38 | Gültekin, A. K. (2019). Kurdish Alevism. Working Paper Series of the HCAS ‘Multiple Secularities – Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities. https://doi.org/10.36730/2020.1.MSBWBM.18 |

| ↑39 | Ahmet Kerim Gültekin (2022) Kemerê Duzgi: The Protector of Dersim (pilgrimage, social transformation, and revitalization of the Raa Haqi religion), British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, DOI: 10.1080/13530194.2022.2126350 |

| ↑40 | Other Customs, Stories, and Beliefs of the Munzur Valley (no date) The Alevis of the Munzur Valley. Available at: http://www.munzurvalley.com/other-customs#customs1 (Accessed: April 2, 2023) |

| ↑41 | Interview with a native Zaza Alevi from Palu, Elazığ province |

| ↑42 | DIMLĪ. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/dimli |

| ↑43 | Mahnaz Moazami, “MAMMALS iii. The Classification of Mammals and the Other Animal Classes according to Zoroastrian Tradition,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2015, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mammals-03-in-zoroastrianism (accessed on 01 April 2023) |